How to use Gatekeeper to define custom policies

I have been thinking for a while about this next topic to talk about, as my idea was always to write about a topic where the current state of articles was minimal (I could, for example, explain how to bootstrap a cluster, but there are already several resources for that end and it could just increase the amount of repetitive knowledge on the internet).

However, pretty recently I have had the chance to use Gatekeeper to define policies for Kubernetes, and I think it is pretty useful to talk, not just about that, but about the concept of policies in Kubernetes in general.

Index:

- Introduction to admission controllers

- Introduction to Open Policies and Gatekeeper

- Gatekeeper policies examples

- Introduction to Kubewarden

- Conclussion

Admission Controllers in Kubernetes

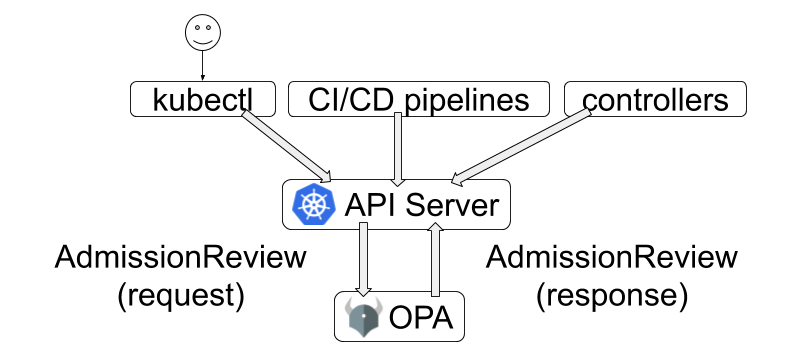

Ok, so let’s start from the beginning, in Kubernetes we have this object (not very well known) called Admission Controller. Their idea is simple, they intercept every request that we send to the Control Panel, and will “ask” an Admission Webhook whether this request is valid or not. But, as we say in my language, a picture is worth a thousand words. So, let’s see this more visually.

So, the Controller intercept the request, but the Webhook is the one to check that a request is valid, according to some specification. If you go into the documentation, you can check that there are several types of this object, but that is not the topic for today.

However, if you deep into them, you can see that they are pretty difficult and required a certain level of domain in order to fully understand them. This article by a Slack Engineering is pretty useful in that regard. In it, the author builds a simple webhook from scratch, and for that, he needs to manage the TLS certificates of the server, write a go program for the policy, …

Of course, nothing that is impossible, and I highly recommend the reading of the article, but we can go a level of abstraction above.

Introducing the Open Policies Agent

This level of abstraction is provided by Open Policies. And we can easily visually it, by checking this image from their webpage.

In case the previous explanation about Admission Controllers was a bit rough for you, you can easily see the usefulness of them now. The core idea is still the same, we will intercept every request and check if we can deploy them or not. But now the work of interacting with the Control Panel is handled by Gatekeeper.

In case the previous explanation about Admission Controllers was a bit rough for you, you can easily see the usefulness of them now. The core idea is still the same, we will intercept every request and check if we can deploy them or not. But now the work of interacting with the Control Panel is handled by Gatekeeper.

And why do I consider it relevant of a post? Well, in the past I talked about securing Kubernetes deployment using Jenkins, and we can also achieve similar results with this methodology, i.e, forbidding certain insecure deployments to happen. I think it is a pretty useful tool, and sadly when I try to investigate them further I didn’t find much useful information out there.

The most useful post is this one by Google. So with that, and playing around a little bit, I tried to generalize them enough in order to explain them here, so anyone can take this lesson to implemented their custom policies according to their needs.

Start writing your policies

The first thing is to install gatekeeper, the documentation helps you with that. But the simplest way for this tutorial to work is just to use:

kubectl apply -f https://raw.githubusercontent.com/open-policy-agent/gatekeeper/master/deploy/gatekeeper.yaml

There are two new objects this introduces, Constrains and Constrains Templates. The latter are the main logic of the policy. While the former define the overall requirements for the policy (range of enforcement, or we can use them to specify parameters). We can use a same template with different constrains, allowing for some level of flexibility.

This Constrains Template is used to check if we have defined limits and requests in our deployment files:

apiVersion: templates.gatekeeper.sh/v1beta1

kind: ConstraintTemplate

metadata:

name: defineresources

spec:

crd:

spec:

names:

kind: DefineResources

targets:

- target: admission.k8s.gatekeeper.sh

rego: |

package defineresources

violation[{"msg": msg, "details": {}}] {

c := input_containers[_]

not c.resources.limits.cpu

msg := "Define resource limits for cpu"

}

violation[{"msg": msg, "details": {}}] {

c := input_containers[_]

not c.resources.limits.memory

msg := "Define resource limits for memory"

}

violation[{"msg": msg, "details": {}}] {

c := input_containers[_]

not c.resources.requests.cpu

msg := "Define resource requests for cpu"

}

violation[{"msg": msg, "details": {}}] {

c := input_containers[_]

not c.resources.requests.memory

msg := "Define resource requests for memory"

}

input_containers[c] {

c := input.review.object.spec.template.spec.containers[_]

}

input_containers[c] {

c := input.review.object.spec.template.spec.initContainers[_]

}

We are retrieving the containers tried to be deployed, and for each one, we are checking if they have defined the fields specified. The reasoning for this policy is that it is best practice to define limits for resources in the containers deployed. If we remember, a simple deployment file YAML for Kubernetes looks like this:

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: shell

labels:

app: shell

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: shell

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: shell

spec:

containers:

- name: shell

image: busybox

resources:

limits:

memory: "500Mi"

cpu: "200m"

requests:

memory: "400Mi"

cpu: "100m"

So, analyzing this along with the template just saw, we get that, in the function input_containers[c] the object

input.review.object

is the file tried to be deployed, knowing that, we then just follow the rest to locate the resources we want to check, following the fields in the YAML shown above:

template.spec.containers[_]

Is the path we follow to get the containers, the [_] is a way of telling to get every container (because we could have several).

Finally, the blocks with:

violation[{“msg”: msg, “details”: {}}] { c := input_containers[_] not c.resources.limits.cpu msg := “Define resource limits for cpu” }

Are the actual rules that are telling to forbid deployments that do not define the resources. The logic is calling the function to get every container, and for every one, if is not define the field resources.limits.cpu, i.e, we have not define limits for the cpu, then forbid this deployment.

Now, to actually enforce this policy, we need a constraints file:

apiVersion: constraints.gatekeeper.sh/v1beta1

kind: DefineResources

metadata:

name: define-resources

spec:

match:

kinds:

- apiGroups: ["apps"]

kinds: ["Deployment"]

We just defined the scope for our rules. In this case, every deployment. The documentation also provided another example that uses parameters.

Finally, we can see how it works in action:

In my repository, you can find more examples using these policies for enforcing also never allowing the use of the latest tag, as well as defining a security context that is not privileged. See it here.

Another level of abstraction - Kubewarden

We could go one step further, in the same way that Gatekeeper is an abstraction above Admission Controllers. We could say Kubewarden is kind of an abstraction above Gatekeeper. A note here, that is a half lie, Kubewarden architecture doesn’t use Gatekeeper. But the idea for my comment is that, now, we don’t need to worry about writing these policies, as they implement an artifact store to share policies. A good reading to their documentation is very clear.

For example, in the documentation we have this policy to forbid privilege pods, we see that the actual policy is retrieved from a registry.

apiVersion: policies.kubewarden.io/v1

kind: ClusterAdmissionPolicy

metadata:

name: psp-capabilities

spec:

policyServer: reserved-instance-for-tenant-a

module: registry://ghcr.io/kubewarden/policies/psp-capabilities:v0.1.9

rules:

- apiGroups: [""]

apiVersions: ["v1"]

resources: ["pods"]

operations:

- CREATE

- UPDATE

mutating: true

settings:

allowed_capabilities:

- CHOWN

required_drop_capabilities:

- NET_ADMIN

The policies shared can be implemented in several languages, and yes, we can share the policies implemented using Gatekeeper (that is the true from my half lie). We just need to compile them using the opa client.

Conclussion

And that is all, I believe practitioners of Kubernetes should be aware of these tools, as Kubernetes is pretty insecure by default. As always, thanks for reading and happy coding.